| Approximately

one in a thousand children aged 0-16 years is visually impaired. This represented

50 children in an average health district with a population of 250,000

(1), a significant proportion of whom has cerebral vision impairment.

Children

with multiple disabilities are frequently referred for refraction and assessment

of visual function, so that parents and carers can be advised about and

understand what the child can and cannot see. The aim of this article is

to outline the principle visual problems and to suggest approaches to their

management.

Assessment

of vision Assessment

of vision

The goals

of assessment are to determine the functional vision available for communication,

education, navigation and other activities, and to advise on methods of

enhancement and compensation to circumvent the visual problems and enhance

development for each individual child.

History

A detailed

history can help compensate for what may necessarily be a limited examination

in these children.

The

profoundly visually impaired child may show evidence of "blind sight" subserved

by the collicular visual system (2, 3). Such children commonly have impaired

movement of all four limbs and appear to react to slowly moving targets

at the side. If they are mobile, they can navigate around obstacles, but

paradoxically may show little evidence of other visual functions.

Severe

visual impairment warrants particular enquiry concerning eye contact, and

the maximum distance from which a silent smile is returned.

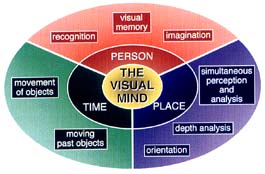

Vision

with an acuity of 6/60 or better necessitates questions directed towards

identifying the following problems (fig 1 above). (4, 5).

Estimating

Visual Function

Function

assessment is carried out with both eyes open.

Visual

behaviour is watched carefully. If the child makes eye contact, move back

gradually until it is lost, in order to establish the distance within which

communication must be made. The fixation pattern if the child looks around

is informative. An alert child repeatedly changes the direction of gaze

to fixate on different targets, whereas the child with impaired vision

appears to look past the examiner with inaccurate and less frequent eye

movements.

Visual

acuity may be estimated in a number of ways, the functional significance

of which needs to be distinguished.

-

VEP

acuity is the minimum target separation which permits VEP signal detection.

-

Detection

acuity (Catford drum or Stycar balls) estimates the minimum size visible.

-

Resolution

acuity (preferential looking cards) is the minimum separation which

allows discrimination.

-

Recognition

acuity (letters or pictures) is the minimum size which facilitates

identification.

Tests

must be appropriate for age and ability. Cardiff cards afford a

rapid and reproducible preferential looking test. The vertical presentation

is helpful in obviating problems due to hemianopia or horizontal nystagmus

and the picture format allows end point detection. Keeler cards

are more suitable for infants who are severely impaired, and may need to

be presented vertically if hemianopia is present or suspected. Recognition

tests can give a lower visual acuity due to crowding.

As

the visual acuity is a measure at maximum contrast and does not estimate

functional vision, the size of educational material must be gauged to allow

maximum speeds of access to information.

Contrast

sensitivity may be estimated using fading optotypes or in younger children,

low contrast faces revealed from behind a cover*. Reduced contrast sensitivity

necessitates the use of high contrast educational material.

Colour

vision is commonly intact although some children can match but not name

colours (colour anomia).

Functional

visual field assessment is carried out binocularly, particularly to elicit

homonymous defects. For the young child, the child's attention is attracted

while a target is introduced from behind in each of the four quadrants,

anticipating a head turn.

For

the older, co-operative child small discreet movements of an extended forefinger

in each of the four quadrants, both singly and on both sides simultaneously,

can be made into a game. Homonymous defects are commonly identified. Inattention

(extinction) is common and functionally can be equally handicapping, e.g.

when crossing roads or attempting to read as the page progressively disappears

for a left hemianopia and jumps into view if it is on the right.

Eye

movement disturbances are common. These include nystagmus (particularly

with additional optic nerve hypoplasia), gaze palsies, oculomotor apraxia

and impaired tracking. The latter may cause children to have no interest

in fast moving cartoons but to prefer TV programmes with limited movement.

Accommodation

and convergence. Some children with brain damage have reduced or absent

accommodation and therefore poor third dimensional tracking which leads

to difficulty overcoming hypermetropia. Retinoscopy prior to cycloplegia

can identify impaired accommodation and reveal manifest hypermetropia not

corrected by the accommodative reflex. The provision of spectacles can

give gratifying results.

Identification

of Higher Visual Processing Disorders

Observation

and a thorough history may reveal and help explain some of the following

types of visual problem (see fig 1).

-

Simultaneous

visual processing problems (9) are common in children with impaired

movement of all four limbs and may manifest as difficulty in finding a

toy on a patterned carpet. Crowding is a clinical manifestation of the

disorder (6). Sorting out a complex visual scene can take a long time.

Such children may read short words easily but can lose track with long

words (4). Enlargement and simplification of educational material, with

sequential presentation against a plain background can be recommended.

-

Recognition

of people, shapes or objects can be selectively impaired particularly in

periventrical leucomalacia (4). A child may be able to see a small toy

in the distance but be unable to recognise a close relative in a group.

Affected children compensate by voice recognition or by recognising shoes

or brooches.

-

Problems

with reading are best assessed by an expert in visual impairment and

education who takes into account the optimal size and lighting required

for a maximum comfortable reading speed and who recognises the nature of

specific reading disorders.

-

Problems

with orientation occur (5) but are not just visual in origin. Children

blind from eye disease can be adept at navigation, while children with

posterior cerebral pathology (particularly on the right) may have good

acuity but get lost and cannot find their toys. Limited mobility and constant

supervision do not give opportunities to develop navigational skills. Education

strategies and mobility training which compensate by using, for example,

language memory for standard routes, are essential.

-

Perception

of movement is most commonly impaired on account of impaired tracking,

but can rarely be a problem in children with damage to the part of the

brain responsible for movement perception, area V5 (5.10).

-

Visual

memory is used for copying tasks which can prove difficult for children

with cerebral visual impairment. In new environments, affected young children

may have impaired face recognition and navigation.

-

Visual

imagination is also observed by the occipital brain, and descriptions

given by parents may indicate good language processing, but difficulties

in handling imagined visual concepts.

-

Lack

of visual attention which is intermittent is common when tiredness,

pre-occupation or distraction lead to behavioural diminution of visual

function. In contract, familiarity with the environment appears to enhance

visual performance.

-

Prolongation

of visual tasks is a common feature. Sufficient time should be given

for a child to demonstrate his or her ability, and the reduced performance

speed recognised.

Profoundly

disabled children may suffer from any of the above problems, but lack of

communication can render it impossible to delineate specific deficiencies.

Conclusion

Vision

Assessment Teams probably provide an optimal service (1). The majority

of such children undergo gradual visual improvement with time, but early

intervention programmes can favourably affect the visual development of

young children with cortical visual impairment. (11-13).

A report

summarising the visual abilities and disabilities with recommendations

for developmental and educational material approaches and, written in plain

English for the parents to give to carers and teachers can be very helpful

in providing a structured addition to the care plan.

Prof

G N Dutton

References

(1) The

Royal College of Ophthalmologists & the British Paediatric Association.

(1994). Ophthalmic services for children. A report of a joint working

party. Services for children who are partially sighted or blind. R.

C. Ophth. BPA. London. pp. 13-14.

(2)

Haigh D. (1993). Chronic disorders of childhood. In: Visual problems

in childhood. Ed: Buckingham T. Butterworth-Heineman Ltd., Oxford.

pp. 47-62.

(3)

Jan JE., Wong PKH., Groenwell M., Flodmark O., Hoyt CS. Travel vision

"Collicular visual system?" Pediatr. Neurol. 1986. 2: 359-62

(4)

Jacobson L., Ek U., Fernell E., Flodmark O., Broberger U. Visual impairment

in preterm children with periventricular leukomalacia - visual, cognitive

& neuropaediatric characteristics related to cerebral imaging.

Devel. Med. Child Neurol. 1996. 38: 724-735.

(5)

Dutton G., Ballantyne J., Boyd G., Bradnam M., Day R., McCulloch D., Mackie

R., Phillips S., Saunders K. Cortical visual dysfunction in children:

a clinical study. Eye 1996. 10: 302-309.

(6)

Pike MG., Holmstrom G., de Vries LS., Pennock JM., Drew KJ., Sonksen PM,

Dubowitz LMS. Patterns of visual impairment associated with lesions

of the pre-term infant brain. Devel. Med. Child Neurol. 1994. 36: 849-862.

(7)

Mercuri E., Atkinson J., Braddick O., Anker S., Nokes L., Cowan F., Rutherford

M., Pennock J., Dubowitz L. Visual function and perinatal focal cerebral

infarction. Arch. Dis. Child 1996. 75: F76-F81.

(8)

Harvey EM., Dobson V., Luna B., Scher MS. Grating and visual field development

in children with intra-ventrical haemorrhage. Devel. Med. Child Neurol.

1997. 39: 305-312.

(9)

Foley J. Central visual disturbances. Devel. Med. Child Neurol.

1987. 29: 116-120.

(10)

Ahmed M., Dutton GN. Cognitive visual dysfunction in a child with cerebral

damage. Devel. Med. Child Neurol. 1996. 38: 736-743.

(11)

Jan J., Sykanda A., Groenveld M. Habilitation and rehabilitation of

visually impaired and blind children. Paediatrician 1990. 17: 202-207.

(12)

Sonksen P.M. Promotion and visual development of severely visually impaired

babies: evaluation of a developmentally based program. Devel. Med.

Child Neurol. 1991. 33: 320-335.

(13)

Sonksen P., Stiff B. Show Me What My Friends Can See. 1991: John

Brown Ltd., Nottingham.

* Available

from Precision Vision, 745 North Harvard Avenue, Villapark, Il. 60191,

USA |